Long COVID, a syndrome brought on by the COVID-19 virus that can affect nearly every organ, the nervous system, cognitive functions, and mental health, could impede the livelihoods and productivity of workers globally, potentially for generations to come. Women of working age—particularly low-paid and frontline workers—are disproportionately affected. To build resilience and recovery across all sectors, business must address inequality.

What’s New

As economies, borders, and workplaces reopen, the desire to return to pre-COVID norms obscures a more complex reality. For many of those who contracted the virus, there will be no "post-pandemic": Numerous studies (including from Nigeria, Egypt, and China) find that individuals who contracted mild or asymptomatic cases are experiencing lasting symptoms with significant implications for their day-to-day lives, including their ability to work.

Understanding of the syndrome known as Long COVID is nascent, with data biased toward hospitalized patients in Western countries. However, the potential scale is alarming: A US study found that almost one quarter (23 percent) of people who contracted the virus in the US in 2020 sought medical treatment for new conditions after they recovered, of which the five most common were pain, breathing difficulties, hyperlipidemia (high levels of fat or cholesterol in the blood), malaise and fatigue, and hypertension.

In a broader study spanning 56 countries, nearly half (45 percent) of people who had been ill for over 28 days with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 reported a reduced work schedule due to ongoing symptoms, with 22 percent not working more than six months after falling ill.

While those affected are of all ages, evidence from around the world (Bangladesh, UK, US) indicates women of working age are disproportionately represented. This compounds and exacerbates the outsized impact of COVID-19 on women, and particularly Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in low-wage jobs, who are already up against a widening employment and equality gap, a greater share of job losses, and an increased care burden. They were also more likely to contract the virus due to greater levels of exposure, and they faced barriers to treatment access and a higher mortality rate.

These hurdles are amplified in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with much less Long COVID research being carried out. Moreover, fewer resources are available for protection, diagnostics, and vaccines, increasing the global divide in managing the pandemic and its fallout.

Dr. Zolelwa Sifumba, who previously worked in a hospital in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, shares her experience of returning to work while coping with Long COVID: “You’re expected to go right back into it, to function at your maximum. Some days you can just carry on. Others, memory and clouded thinking are a huge issue, making it very hard to work and trust oneself while working. My anxiety went through the roof. I struggled with clinical decisions—when to start a drip, when to start CPR, which drug, what dose...it was pretty much a gamble! Apps on my phone helped me keep track. It would be better to have a senior [physician] there to work with you, but given workforce pressures, you’re often alone.”

The World Bank estimates COVID-19 will have pushed around 120 million people into extreme poverty by the end of 2021, without accounting for the impact of Long COVID. Recent years have shown how closely widening equality gaps, polarizing stereotypes, and social unrest are knit. Businesses and governments cannot afford to wait for a more comprehensive understanding of Long COVID to emerge. Swift action to protect, support, and empower those affected by the syndrome will make the difference between a resilient workforce and society and a continually ailing one.

Signals of Change

The US Congress is providing US$1.15 billion over a four-year period to support a major study by the National Institutes of Health into the prolonged health consequences of Long COVID, including the causes, symptoms, and recovery spectrum across the population, and whether the infection can trigger changes in the body that increase the risk of other conditions.

The UK’s Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) has provided guidelines for employers and employees about sickness and absence due to Long COVID, noting that it cannot yet be deemed a disability. It includes recommendations for a phased return to work, including reasonable adjustments to the workplace or working hours.

The UK is investing GBP£100 million in care for those with Long COVID, including pediatric hubs to support children and young people. This is on top of a GBP£34 million investment in specialist clinics across the country. As of March 1, 2021, 1.1 million people in the UK had reported suffering from Long COVID, including an estimated 7-8 percent of children aged 2-16.

A Hong Kong study published in the journal Gut has found COVID-19 significantly alters the gut microbiome in samples taken up to 30 days after the infection had cleared, suggesting a possible correlation between microbiome composition and ongoing symptoms. The bacterial compositions were comparable to those linked with inflammatory disease.

Fast Forward to 2025

For decades, we struggled to get any sustained interest in or action on our working conditions. The 2013 Rana Plaza disaster got activists and some well-meaning brands fired up, so to speak, for better pay and working conditions...

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Implications for Sustainable Business

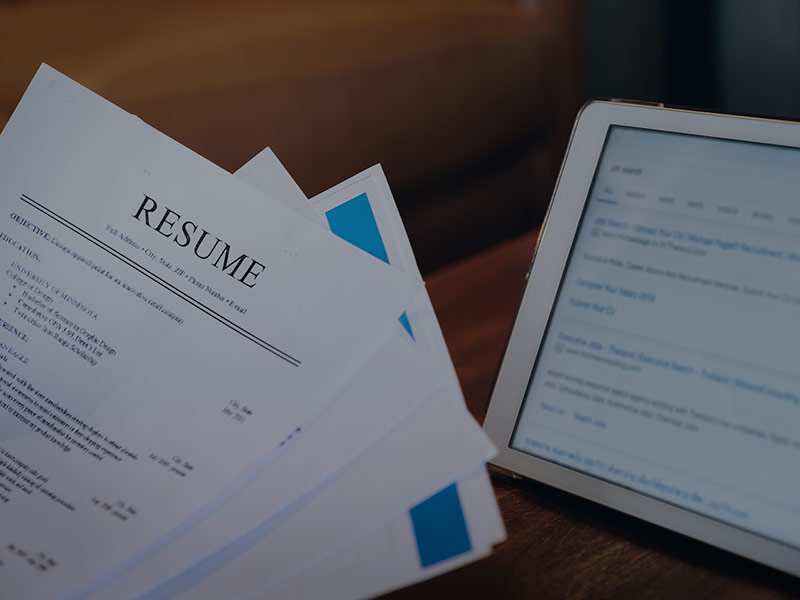

Businesses face a range of workforce challenges due to Long COVID. In the near term, these include direct ramifications for productivity and quality of output. Already, there are extensive reports of redundancies and early retirement, both voluntary and involuntary.

Then there’s the impact of presenteeism, where workers persist through symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, brain fog, and anxiety due to lack of support in the workplace and for fear of losing income or opportunities. All of these factors will play out across all levels, from the least valued and protected to the C-Suite.

Pressure to support those with Long COVID through significant shifts in workplace policy and practice could come from regulation, the public, competitors, collaborators, and from increasingly ESG-minded investors monitoring well-being at work. This is all part of a wider shift in the social contract between business and society.

Companies need to think about disability and inclusion differently: more flexibility around who’s working when, more paid time off, more empathy. A large percent of the population now need significant support to find dignity at work.

The legal and insurance sectors are also waking up to their role in protecting public and private interests. Insurers are launching group income protection schemes to support the reintegration of employees with Long COVID, offering psychological support alongside payouts as well as income protection schemes for individuals, families, and small businesses, recognizing that the most vulnerable are informal, temporary, and freelance workers. Beyond such schemes, employees’ rights could largely be determined by whether or not they are classified as disabled.

Economies that facilitate the integration of people with disabilities bring significant economic and social benefits by maximizing workforce potential, overcoming societal misconceptions, reducing labor market scarring, and lessening demand for welfare payments. The International Labour Organization advises companies to express clear support for disability inclusion from the top, remove recruitment barriers, and take an accessibility audit. In France, companies that don’t meet a quota for disability recruitment have to pay a higher tax rate.

Impacts of a sharp rise in Long COVID on disability inclusion could go at least two ways: increased acceptance and understanding thanks to a proliferation of inclusive policies that open minds as well as doors, or fewer opportunities spread among many more contenders as discrimination and stigma increase barriers.

Leadership on diversity and inclusion at work, through greater flexibility, accessibility, mental and physical health support, and empathy, would see cascading benefits for all workers. For instance, a flexible system that allows employees to swap shifts, combine sick days and holidays as required, or distribute four-day weeks over the course of a year would help address the issue of intermittent and unforeseeable absences and also lower barriers for parents and carers, increasing the gender balance.

There are many barriers to change. One is a lack of representation among leadership: Very rarely does someone with a chronic illness or disability in a leadership position come out and disclose that. People need to feel comfortable enough to ask for support. This is compounded by a lack of knowledge and understanding. Many businesses still see inclusion as a chore, not an opportunity.

The business benefits of inclusivity are well documented, but chronic illness and disability have often been overlooked. In a study by Accenture and DisabilityIn, disability champions achieved on average 28 percent higher revenue, double the net income, and 30 percent higher economic profit margins over a four-year period. They also achieved 90 percent higher retention rates and a 72 percent increase in employee productivity.

Conversely, without action, companies also face a reduced, less diverse talent pipeline, hampering both their productivity and capacity for innovation—a key enabler for the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Even with policies and practices in place, companies may need to employ more staff than before to maintain the same level of output or nurture relationships with temp agencies. The gig economy could surge in response to intermittent need, but temporary and independent workers are also the most vulnerable to ongoing loss of employment and income. Building resilience across sectors and economies will therefore require businesses to look beyond direct employees to safeguard and support workers throughout their value chains.

![]()

Previous issue:

Carbon Trade Wars?

![]()

Next issue:

Satellites Remaking Supply Chains