Tackling forced labor is becoming a key component of trade legislation. The global regulatory environment to combat forced labor has gained momentum as it shifts from a reporting requirement to mandatory due diligence to an enforceable legal trade requirement in some countries. As more enforceable legislation emerges, borders are becoming less open to products associated with forced labor.

What's New

In the past decade, several countries and states have reviewed and implemented new requirements on forced labor that extend into supply chains and impact the ability of companies to import goods into traditional consumption markets. This began with the California Transparency Supply Chain Act in 2012 and the Modern Slavery Acts (MSAs) in the UK and Australia in 2015 and 2018, respectively. While the MSAs have brought some focus to the issue, these reporting requirements have been unenforceable.

Now, a new wave of forced labor legislation that has more teeth is emerging, including upcoming mandatory human rights due diligence legislation in the E.U. and labor prohibitions in trade agreements such as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

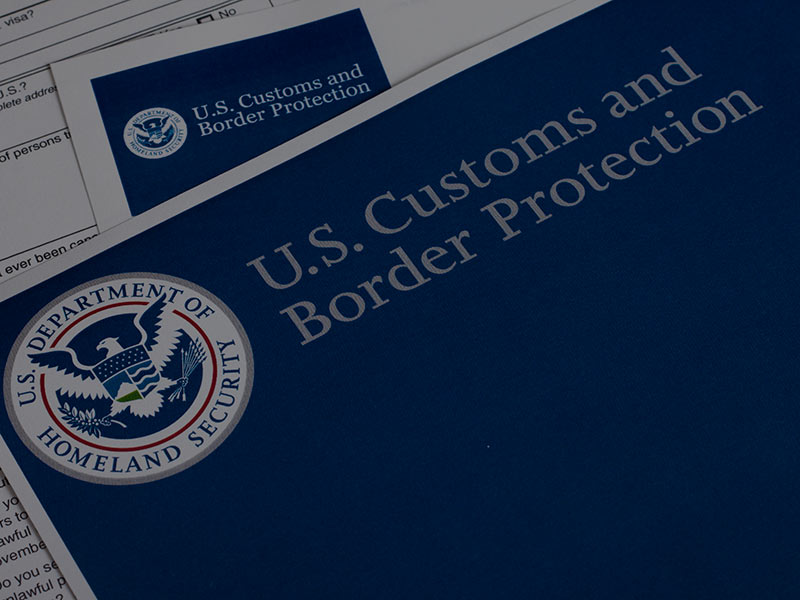

The U.S. has also begun using trade legislation as part of an enforcement-focused approach to forced labor under the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015, which came into effect in 2016. In 2018, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (US CBP) created the Forced Labor Division which expanded its authority to act and better enforce the new policy.

Since 2019, the US CBP has begun to issue an increased number of Withhold Release Orders (WRO) of goods that had ‘reasonable suspicion’ of being produced with forced labor, based on allegations of forced labor submitted by the general public and civil society as well as from self-initiated investigations. This has resulted in a new awareness of the link between forced labor and business. And as this awareness grows, the number of allegations—and subsequently enforcements—continues to increase.

This new focus on human rights within global trade has resulted in an increase in WROs for goods/entities produced in certain countries, particularly China. The US CBP has also halted imports from several other countries, including Malaysian goods such as palm oil and medical disposable gloves.

In addition, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Uyghur Human Rights Act and the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in September 2020 with bipartisan support, and they await a vote in the Senate. The latter, known as the ‘Uyghur Bill,’ would ban imported goods made with forced labor in China’s Xinjiang region. Some U.S. companies say the bill will be highly disruptive for businesses with supply chains that are heavily dependent on China, and they are lobbying for a less stringent version of the bill.

There is little expectation that the focus on forced labor in trade will wane under the Biden administration. Instead, heightened interest in forced labor among civil society and an increasingly enforceable regulatory framework may continue to propel this issue forward with an even broader geographic scope. This will be aided by technology developments that are enabling more surveillance and transparency in supply chains than ever before.

Signals of Change

In August 2020, the US CBP issued its first fine under the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act. The US$575,000 fine was issued against the importer Pure Circle U.S.A., Inc. after an investigation revealed that Pure Circle U.S.A., Inc. had imported at least twenty shipments of stevia powder and derivatives produced from stevia leaves that were processed with forced labor in China. The CBP initiated the investigation following an allegation from a NGO.

Nine of the unprecedented 14 WROs issued by the US CBP in 2020 were on products originating in China. In September 2020 alone, the US CBP issued five WROs for goods from specific producers in the Xinjiang area of China with products ranging from hair products to apparel. Since 2016, 14 WROs have been issues on Chinese goods; no WROs were issued between 1996-2015. A WRO has also been issued for any product made with labor from No. 4 Vocational Skills Education Training Center, which U.S. Homeland Security Acting Deputy Secretary Ken Cuccinelli described as a center of forced labor.

The new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), came into effect on July 1, 2020. The trade agreement includes a number of new prohibitions on forced labor including stronger enforcement provisions like the Rapid Response Mechanism and the prohibit of any party to import goods produced in whole or in part by forced or compulsory labor, including forced or compulsory child labor.

Australia has begun to ban cargo ships from entering Australia for breaches of the Maritime Labour Convention, including underpaying and over-contracting seafarers. As many as six ships have been banned from entering the country in 2019 and 2020. In October 2020, a ship carrying Japanese cars bound for Australia was arrested and detained as it was revealed it contained over-contract seafarers.

Fast Forward to 2025

Even though we never had issues with forced labor at my garment factory, I knew it had been a problem in the industry. About five years ago...

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Business Implications

In the short term, business will have to enhance their own governance structures and carry out robust human rights due diligence to mitigate the risk of forced labor in their supply chains. This will include identifying the locations and value chains where forced labor is likely to be present and developing measures, in partnership with suppliers, to prevent, mitigate, and remediate forced labor.

While businesses have had to grapple with reputational risks of being associated with forced labor in recent years, the financial and operational consequences are growing. This extends beyond tier 1 suppliers, as business will need to have enhanced transparency deeper into their supply chains, seek out responsible and transparent primary resource producers, and have multiple tiers of suppliers adhere to codes of conduct and human rights due diligence processes.

Alongside enhanced transparency, this shift may also call into question procurement practices and the current global trading model that are often implicated in the use of forced labor. Current trading schemes generate opacity in global supply chains, as players are mostly buying based on price volatility and shifting suppliers on a regular basis at all tiers.

Businesses, including producers, processors, consumer goods, traders, and financial institutions, will need to develop and propose an alternative way of operating global trade. This new business model must provide transparency and responsibility along with profitability for the goods and services that are purchased on the global market. Strengthening relationships with suppliers and encouraging value-added partnerships that demonstrate compliance will become fundamental.

To support such evolution, a new range of tech-enabled products and services can be expected to meet the increased demand for transparency and traceability, along with new and extended mechanisms for whistle-blowing.

While these changes are likely to impact all industries, those with agricultural or mining inputs are particularly at risk—such as food and beverage, consumer goods, extractives, and technology. A knock-on effect may occur within the financial sector, whereby processing the proceeds of a crime, in this case goods produced with forced labor, could be interpreted as money laundering and could implicate banks providing trade finance to supply chains with forced labor.

Sustainability Implications

Sustainability teams will need to work closely with procurement, compliance, legal, and public affairs teams to mitigate risks as this issue evolves and forced labor emerges as a supply chain and business continuity risk.

The men and women of U.S. Customs and Border Protection are working hard every day to identify and prevent goods made with forced labor from entering the United States. Forced labor is modern slavery, and companies have a responsibility to eliminate it from their supply chains. There are serious financial, reputational, and legal costs associated with attempting to import goods made with forced labor into the United States. CBP urges U.S. businesses to exercise reasonable care, as the burden of proof is their responsibility.

Business will need the appropriate systems and human rights due diligence processes and practices to be in place in their own workplaces and supply chains to mitigate the risk of forced labor. Processes and practices include grievance mechanisms and governance structures. In addition, businesses will also need to re-examine supply chain practices that may facilitate forced labor in their supply chain, including purchasing practices and supply chain finance.

Sustainability teams should also look to create solutions with supply chain partners and other civil society groups that include workers in their design and implementation, such as enabling responsible recruitment practices.

To address the systemic issues underpinning forced labor, sustainability teams may need to engage in industry or cross-industry collaborations to improve trade practices and provide support to suppliers. Processes such as strategic sourcing and reverse sourcing could provide mechanisms to build stronger partnerships with suppliers that enhance transparency, ensure compliance and mitigate risks going forward.

![]()

Previous issue:

Digital Passports for Clothing

![]()

Next issue:

Business Reckoning on Reparations