Successful lawsuits and constitutional changes in several countries, alongside a widely supported draft legal definition for “ecocide” by prominent International Criminal Court jurists, indicate that the “rights of nature,” a concept rooted in Indigenous worldviews, is being extended into criminal law. Courts and legislatures are increasingly extending legal personhood to rivers, water tables and oceans, forests, wildlife, and whole ecosystems, granting them a defendable right not to be harmed and placing them on the same legal footing as corporations. This could increase the amount and severity of litigation brought against companies by civil society, accusing them of degrading the environment, and present them with a new enforceable duty of care towards nature.

What’s New

“Rights of nature” laws recognize that ecosystems, on which all human systems depend, must be allowed to exist, flourish, and evolve free from harm by human actions. They draw on an Indigenous understanding of the world, founded in spiritual beliefs, that recognizes the interdependence of all natural entities, including humans, and an influential 1972 paper by the US law professor Christopher Stone, “Should Trees Have Standing?” which argued that nature has fundamental legal rights.

Western legal frameworks with anthropocentric foundations have traditionally been a barrier to the enforcement of nature’s rights, treating nature purely as a resource. Today, however, there is significant global momentum behind emerging concepts such as “Earth Jurisprudence” and “Wild Law,” in what would potentially be a paradigm shift toward a nature-centric approach.

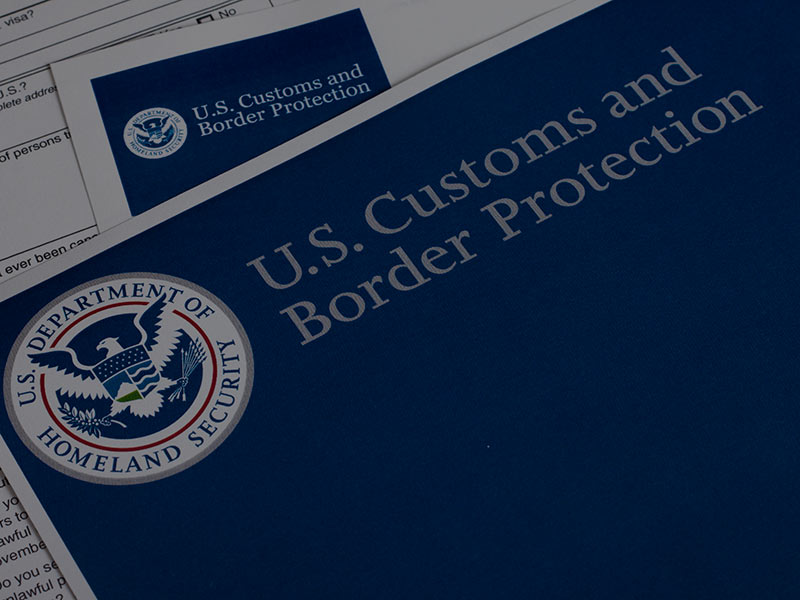

In perhaps the clearest sign of this, an international legal team, co-led by barrister and professor Philippe Sands QC and former UN international prosecutor Dior Fall Sow, has drawn up a draft definition for “ecocide.” Its purpose is to amend the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) with the addition of a fifth international crime alongside genocide and crimes against humanity. It defines ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts,” in which the environment encompasses “the earth, its biosphere, cryosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere, as well as outer space.” If adopted by the ICC, it would be the only international crime in which direct human harm is not a prerequisite for prosecution, and individuals responsible for these acts would be subject to criminal investigation. Some legal scholars see this leveling of the legal playing field between all life forms as a logical extension of establishing rights of nature.

President Macron, the Belgian Government, and Pope Francis have all backed the idea of an ecocide law, as have the Pacific islands of Vanuatu and the Maldives, which are particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels. But for the draft law to be adopted by the ICC, one of the Rome Statute’s signatory nations will need to submit it to the UN Secretary General for consideration, thereby triggering a vote at the ICC’s annual assembly. Even if the vote is successful, it could still take years or decades to complete the amendment to the ICC’s founding treaty.

Meanwhile, throughout the world, rights of nature are making legal headway. Whether it’s through local laws, constitutional amendments, treaty agreements, or judicial decisions—these rights now exist in around 30 countries. For instance, the New Zealand parliament granted personhood status to the Whanganui River in 2017, which is revered by the Māori. In 2019, the High Court of Bangladesh followed suit by recognizing the Turag River as a living entity with legal rights, which were subsequently applied to all rivers in the country. But few countries have gone as far as Ecuador, which in 2008 became the first country in the world to enshrine the rights of Pachamama, or Mother Earth, in its constitution.

Since then, Ecuador has become the global epicenter of rights of nature litigation. But while there have been notable victories in provincial courts, this hasn’t always translated into remedial action on the ground. A significant counterforce is the government’s desire to generate revenue from the country’s mining sector. In 2017, it announced new concessions for mining exploration over 2.9 million hectares of the country—an increase of 300 percent. Many of these concessions are in protected forests and Indigenous territories, headwater ecosystems, and biodiversity hotspots.

And so, despite Ecuador’s groundbreaking constitution, the balance of power seems ultimately to lie with the state and moneyed corporations. This imbalance appears to be feeding the trend for lower court decisions in favor of nature’s rights to be overturned by higher courts. The fact that the government has appealed several rights of nature victories visibly undermines its commitment to the constitution. Some judges may also be coming under pressure not to scare off much-needed foreign investment.

Even when attempts to defend the rights of nature fail in the courts, they can help to generate public support for the cause—which, as the abolitionist, civil rights, and women’s suffrage movements proved, is half the battle.

Grassroots action is also raising public awareness of the rights of nature in the US. In 2020, a coalition of farmworkers, farmers, and conservationists filed a federal lawsuit to challenge the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) reapproval of glyphosate, citing its risks to pollinators, butterflies, and soil health as well as to the health of farmworkers and their children. The EPA has asked the federal court for time to review the ecological impacts while standing by its finding that the pesticide in question, Roundup, does not pose major risks to human health.

Efforts to inscribe the rights of nature movement in law share an underlying objective with efforts to recognize the human right to a healthy environment and rights of future generations, enabling action to drive equitable outcomes without direct damage to individuals. For instance, in October 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) unanimously voted to recognize a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a universal right, following a campaign led by 13,000 civil society organizations and Indigenous peoples’ groups, 90,000 children, private sector stakeholders, and human rights institutions.

Such efforts signal a shift in how we value the future life of our planet and the species that depend on it, raising questions about who gets to determine that value in the here and now. Do projects that will generate societal or economic gains today justify an uncertain degree of pain tomorrow? And when should the rights of nature, non-human species, or unborn generations take precedence over rights to land or other resources? Such questions underpin efforts to revise social discount rates, which are used to work out how much today’s society should invest in trying to limit the impacts of climate change in the future. There are no easy answers.

Signals of Change

In March 2021, the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs published a study exploring the concept of “Rights of Nature” and its different implications for legal philosophy and international agreements as well as legislation. While recognizing the current problem of weak enforcement, it emphasizes the increased potential for constitutional changes in the EU regarding the intrinsic value of biodiversity and principles of ecological integrity, leading to stricter regulatory requirements.

A tribal nation in the US, the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, has brought a “rights of nature” claim against the state of Minnesota for its approval of an oil pipeline replacement, now complete, that consumed 5 billion gallons of water. The lawsuit asserts that the reduced water levels violated the rights of wild rice. Moreover, a long-established treaty gives White Earth the right to gather wild rice off reservation land, strengthening the lawsuit. The federal court ruling could see tribal law used to block projects beyond reservations.

In Ecuador, Los Cedros Protected Forest authorities took Cornerstone Capital Resources and the Ecuadorian state mining company ENAMI to court in 2019 for its plans to explore for copper and gold on the protected reserve. Los Cedros won; however, the government has since appealed the verdict. If the Constitutional Court upholds the rights of Los Cedros, it could set a precedent for defending all 186 protected forests in Ecuador from mining.

Following a public vote in 2020, 89 percent of Orange County voters in the US approved the “Right to Clean Water” Charter Amendment, which recognizes both the rights of the municipality’s waterways to be protected against pollution and maintain healthy ecosystems as well as the rights of residents to clean water. Those who backed the measure included the League of Women Voters and the Democratic Party.

The Federal Court of Australia ruled that when considering whether to approve the expansion of a coal mine, the nation’s environment minister had a duty to take reasonable care that children under the age of 18 would not be harmed or killed by carbon dioxide emissions. The class action suit, brought by eight teenagers and an octogenarian nun, argued that the expansion of the coal mine would contribute to climate change and endanger their future. It is thought to be the first time that a court has ordered a government to protect young people from climate change.

Fast Forward to 2025

The Sandburton River was my first non-human client. This was back in the days when the rights of nature were still something of a niche legal area...

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Implications for Sustainable Business

As rights of nature expand, so will the compliance and monitoring processes that companies will need to undertake. Businesses can expect expanding regulation on environmental impacts just as for human rights impacts, including mandatory due diligence process and potential trade barriers for non-compliance. Implications could reach across their entire current and future portfolios, including feedstock origin, potentially demanding a step change in traceability. All projects might require proof that they will not violate the rights of nature (through damage to biodiversity, ecosystems, and ecological cycles), requiring resources for more detailed Environmental Impact Assessments. Permits, licenses, and other approvals could also come with stricter rights-based conditions. In mining, for instance, independent cost-benefit analysis may be required to obtain exploration permits. The fact that copper and other metals are essential components of wind turbines and other green technologies raises the complicated question of ethical trade-offs regarding mining’s role in tackling climate change vs. the rights of nature.

All this means building capacity to conduct nature rights impact assessments across the value chain: at the product level, with tier 2 and 3 suppliers, and at the point of extraction or production for raw materials. For procurement, collaborative action will be required to ensure consistent metrics and standards among supplier impact assessments. End-of-life management will also come under scrutiny, affecting many mainstream products, from batteries and electronics to plastics. This level of transparency and traceability could be challenging and require new governance structures and processes to monitor nature impacts. These could be aligned with the upcoming Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), which will support business in assessing emerging nature-related risks and opportunities. For instance, agribusinesses will need to assess exactly how runoff from their operations could affect local lakes and rivers.

Solving these emerging challenges could start with increased investment in technological solutions, such as satellite sensing and data analysis. Another possibility is “ecological impact tracing,” whereby the impacts of a particular production method or system on nature and ecology would be investigated, analyzed, and recorded. Combined with the rise of smart sensors for detecting everything from particles and chemicals to water flow and biodiversity loss, such an investigation might well unearth impacts beyond the bounds of traditional impact assessments.

Adding to the complexity and need for transparency are indications that the rights of nature could be applied across borders and will likely be adopted at varying rates globally. In 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights published a landmark Advisory Opinion on the environment and human rights, which ruled that states must take measures to prevent significant environmental harm to individuals inside—and outside—their territory. A legal responsibility not to impinge on nature’s rights across borders would have implications for value chains and traceable impacts like transborder air pollution. Germany’s new mandatory supply chain due diligence applies to both human rights and environmental protection, indicating a value chain approach to national laws. The EU is considering similar legislation to make the protection of human rights and the environment in supply chains a legal requirement.

Moreover, businesses with international value chains may need to comply with a variety of rights-based laws across different territories. For now, there’s no consensus on how to adopt rights-based laws, no standardized definition for terms such as “biodiversity” and “nature,” and no shared understanding of their vulnerabilities. “What works in one country [or] jurisdiction may not work in another due to a myriad of factors, including how the legal system works, societal values, political will, and so on,” says Michelle Bender, ocean campaigns director at the Earth Law Center.

To address this, frameworks for compliance, such as indicators of abuse of nature’s rights, and remediation processes need to be established. Remediation in particular may have lasting financial impacts for businesses, specifically in the context of irreversible environmental damage. One possibility cited in a European Parliament study on rights of nature is a remediation fund for the restoration of damaged areas and habitats, raised through taxation of environmentally hazardous industries as well as sanction fees for breaches of environmental law.

Beyond restoration costs, remediation raises the thorny question of how we “price” nature, both for its intrinsic value and ecosystem services. The Natural Capital Protocol, backed by the IUCN’s Global Business and Biodiversity Programme and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, offers a standardized framework, and guides for applying it have been developed for the apparel and food and beverage sectors. One profitable approach is payment for ecosystem services, incentivizing businesses to manage land in such a way that enhances nature’s functions, such as providing clean water and air, replenishing soil nutrients, and maintaining biodiversity.

While rights of nature laws are still being developed, companies have the chance to engage with and influence the process, opening a dialogue with other advocates, such as ecologists, activists, academics, lawyers, and Indigenous Peoples. In fact, companies such as Lush and Patagonia already support legal standing for nature by funding law centers and environmental groups promoting this approach. This not only allows them to draw on the expertise of these groups to ensure their business practices will align with a rights-based legislative environment—it puts them on the right side of a movement that could increasingly win public support and improve their reputation.

![]()

Previous issue:

The Global Population Slowdown

![]()

Next issue:

Central Banks Embrace Digital Currencies