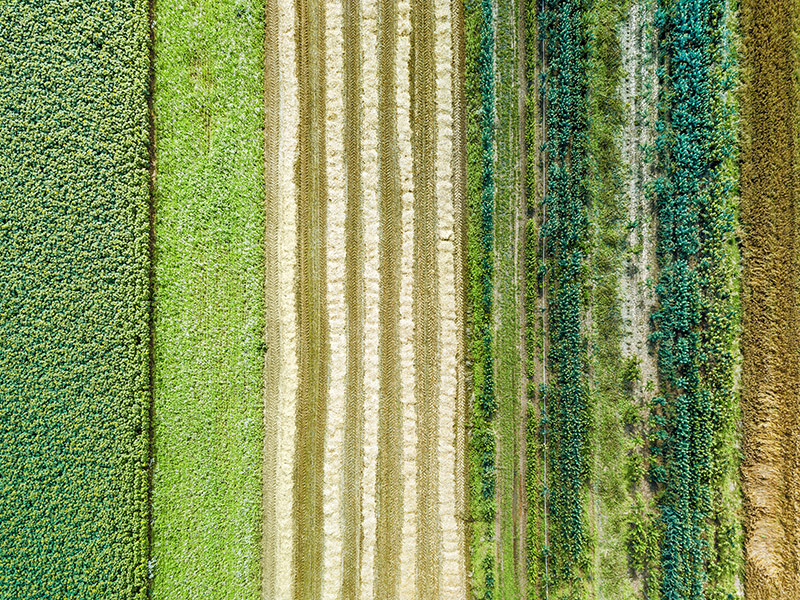

The accelerating energy transition is prompting a global scramble to secure critical mineral supply chains. A stable supply of these minerals will be crucial for countries to meet both their climate ambitions and increased demand in consumer goods. In response, countries are looking to new trading partners, stockpiling, domestic exploration, innovations in mineral extraction, and the circular economy as a suite of solutions. But, given the drastic increases in demand expected, supply will be constrained by geopolitical tensions and ongoing social and environmental challenges in traditional terrestrial mining.

What’s New

As the transition to a low-carbon economy accelerates faster than predicted, demand for the minerals that support the energy transition is ramping up. Countries are growing more dependent on rare earth elements and critical minerals to support their climate commitments and economies.

While rare earth elements have faced supply constraints for some time, this is extending to the broader class of “critical minerals,” which are necessary for the energy transition and consumer markets.

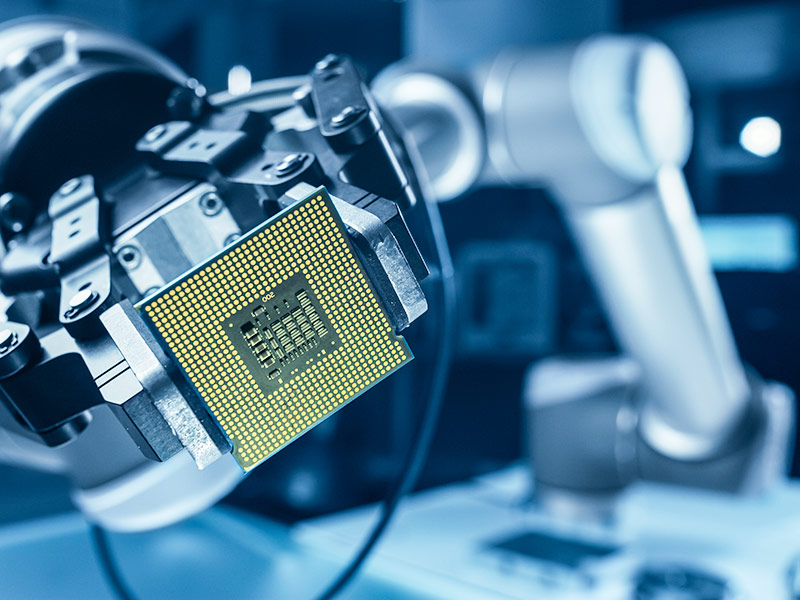

Battery minerals—in particular, cobalt and lithium—are facing increased demand, shifts in supply chain dynamics, and a potential global shortage driven by the energy transition and growing electric vehicle use. Demand for lithium-ion batteries is projected to grow by 500 percent between now and 2025. The EU has announced that from 2035, all new registered vehicles will be required to be net-zero. In a 2050 scenario where 100 percent of energy is renewable, demand for lithium would be 280 percent of currently documented deposits and 426 percent of cobalt deposits.

As a result, a global scramble is unfolding to control and expand the critical minerals supply, with China currently well in the lead. China is the world’s largest producer of many of these minerals, either through investment or outright ownership of mines globally (predominantly in Africa and Latin America) and domestic processing capabilities.

The concentration of production and processing operations for critical minerals in a small number of countries makes the supply especially vulnerable to geopolitical risks and possible export restrictions. China discussed export controls on rare earth elements and has leveraged access to critical minerals in geopolitical disputes in the past. This is a growing concern for the US and other Western countries, given mounting tensions with China.

Against this backdrop, Western countries are racing to stockpile critical minerals on the advice of the International Energy Agency—leading to a reshuffling of trading partners and exploration of new domestic or expanded alternative sources. This includes exploring new methods of extraction, such as deep-sea mining and volcanic mining, that do not have the same social or environmental challenges as existing practices—though face altogether new risks and unknowns. New technologies for reprocessing mine tailings are also being developed. Critical mineral supply chains could also see increased government intervention such as nationalization or increased taxes.

The circular economy, including the recycling of battery minerals, is also emerging as a strategically important investment.

However, even with alternative sources and circularity, the sheer size of future demand means that expansion of mining activities is still necessary. Meeting stakeholder expectations on ESG issues will be challenging, especially given existing social and environmental challenges, such as pollution and modern slavery in cobalt supply chains and water stress and indigenous rights violations in lithium supply chains. This tension could result in additional pressure on the supply and cost of critical minerals or could lead to a reneging on commitments to responsible mining.

To ensure a sustainable and available supply for future demand, aligning the current set of fragmented standards to establish a coordinated set of global principles on responsible mining is critical. Crucially, these need to be acceptable to everyone, from communities and civil society to mining companies, buyers, and governments.

Signals of Change

In March 2021, TES—a Singaporean e-waste recycler—opened a new battery recycling facility capable of recycling up to 14 tons of lithium batteries per day and recovering up to 90 percent of precious metals such as lithium and cobalt from lithium-ion batteries. Singapore has also introduced an extended producer responsibility system for electronic goods, which came into effect in July 2021.

In June 2021, the Biden-Harris Administration’s 100-day supply chain review report identified the need to invest in sustainable domestic and international production, refining, and recycling of critical minerals while ensuring strong environmental and labor standards. As a result, the US has outlined a plan to address strategic supply chain issues, which includes using large-capacity batteries in electric vehicles and giving sourcing preference to trusted allies, such as Australia.

In June 2021, Canada and the EU announced a new strategic partnership on critical minerals that enables both regions to decrease the dependence on China for critical minerals.

Spurred on by increased demand for critical minerals and the COVID-19 economic downturn, Pacific Island nations have begun sponsoring mining companies to take out licenses for deep-sea mining. Initial research indicates the impacts of deep-sea mining would be “extensive, severe, and last for generations, causing essentially irreversible species loss.” Civil society and scientific groups are calling for a moratorium to allow scientists more time to determine the risks.

Fast Forward to 2025

With the EU announcing a target of having 30 million electric vehicles by 2030, we were really excited for our industry...

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Implications for Sustainable Business

As governments and mining companies address geopolitical risk and scramble to secure supplies, it is important that sourcing communities do not get caught in the crossfire. Responsible sourcing will become more challenging as demand for critical minerals increases to levels beyond available supply. The urgency to secure more critical minerals may lead to rapid expansion into new mining areas, with increased environmental and social risks both domestically and abroad.

At the same time, it’s important that the industry not lose sight of engaging existing sourcing communities to mitigate social and environmental challenges.

As all industries pursue climate action and digitalization, critical minerals in batteries are more likely to be a part of their supply chains, particularly for automotive, electronics, energy, and even consumer goods. Companies procuring electric vehicles or renewable energy solutions will face mounting consumer and investor pressure as demand comes up against stakeholder expectations. They will need to implement heightened due diligence procedures to ensure inputs are sourced in a way that protects human rights and the natural environment.

These industries will need to provide a clear signal of their sustainable sourcing standards for critical minerals and their commitments to responsible mining. Crucially, companies sourcing these minerals need to work closely with mining organizations, standard-setters, and civil society to ensure that standards are not only appropriate but also attainable, and they need to ensure a reliable and responsible supply chain. New explorations or reshoring must also include a regulatory framework that works with the private sector and ensures adherence to standards.

Even with new extraction methods and circularity, the hard truth is that current mining practices will remain dominant methods of producing metals and minerals, and we need to focus our efforts on solving the challenges in these supply chains. I’m optimistic that, through coordinated global action, we can get the majority of metals through good responsible mining standards, but this will require collaboration among buyers, miners, investors, civil society, and standard-setters. The challenge is that geopolitics could get in the way of this collaboration. To avoid this, we need politically neutral industry convenors and alignment on a single global standard for responsible mining.

Furthermore, as the circular economy for critical minerals increases, there is a danger of recycling activities moving to poorly regulated markets or areas with existing human rights abuses. It will be important for companies to establish mineral recycling processes with social and environmental safeguards and regulations.

Companies should consider the geopolitical risks facing their products that rely on batteries as well as their climate commitments that rely on renewable energy and electric vehicles. Although this is beyond the control of any one company to mitigate, companies dependent on critical minerals have a vested interest in a stable geopolitical environment and should advocate for industry collaboration that enables stability and global standards of responsibility. Companies can also look to invest in initiatives that strengthen resource management and incentivize sustainable mining operations as well as in closing knowledge and technology gaps.

If tensions continue to rise, renewable energy, electric vehicle, and consumer goods industries could face constrained access to critical mineral inputs. Global access to batteries for electric vehicles and grid storage is essential for the energy transition needed in every country. If battery storage is unavailable and price-competitive in every market, we cannot fully address the systemic risk of climate change. A conflict-filled market for critical minerals could stall the energy transition in certain countries, placing all businesses globally at further risk of climate impacts.

![]()

Previous issue:

Satellites Remaking Supply Chains

![]()

Next issue:

The Global Population Slowdown